Hg Team of scientists. From Left to Right, bottom row: Dr. Geraldine Nogaro, Katlin Bowman, Lisa Romas, Melissa Tabatchnick, Michael Finiguerra, Kathleen Munson, Susan Gichuki. Left to right, top row: Dr. Carl Laborg, Dr. Chad Hammerschmidt, Tristan Kading, Allan Hutchins, Lynne Butler, Dr. William Fitzgerald, Prentiss Balcom. Absent - Jenay Guardiani Aunkst.

Hg Team of scientists. From Left to Right, bottom row: Dr. Geraldine Nogaro, Katlin Bowman, Lisa Romas, Melissa Tabatchnick, Michael Finiguerra, Kathleen Munson, Susan Gichuki. Left to right, top row: Dr. Carl Laborg, Dr. Chad Hammerschmidt, Tristan Kading, Allan Hutchins, Lynne Butler, Dr. William Fitzgerald, Prentiss Balcom. Absent - Jenay Guardiani Aunkst.

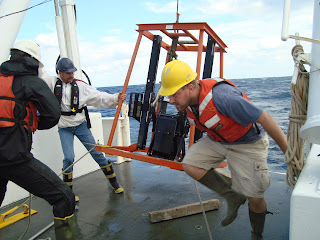

Gale wind warning toward the end of the cruise

Jenay packing.

Jenay packing. Melissa packing up her room.

Melissa packing up her room.Well, we returned to port earlier than anticipated due to the gale winds and 20 foot swells. Much to my chagrin, I spent my last few days in the hold, sleeping and trying to quell my motion sickness. By the end of the cruise, I wanted so badly to stand on solid ground! This was in stark contrast to the previous cruise when I did not want to leave the ship! It's amazing how we are always subject to the power of mother nature. Although she made this cruise more difficult, it will prepare us for yet another cruise that the WSU team will be taking in June 2010.

We would like to extend our appreciation to the National Science Foundation for funding our research on mercury cycling in the oceans. Thank you, NSF!

~Lisa

Just before sunrise...

Just before sunrise... The sun creeping up in the sky to begin the day...

The sun creeping up in the sky to begin the day...